Abstract

Background

As social media are evolving rapidly online support groups (OSG) are becoming increasingly important for patients. Therefore, the aim of our study was to compare the users of traditional face-to-face support groups and OSG.

Patients and methods

We performed a cross-sectional comparison study of all regional face-to-face support groups and the largest OSG in Germany. By applying validated instruments, the survey covered sociodemographic and disease-related information, decision-making habits, psychological aspects, and quality of life.

Results

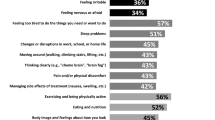

We analyzed the complete data of 955 patients visiting face-to-face support groups and 686 patients using OSG. Patients using OSG were 6 years younger (65.3 vs. 71.5 years; p < 0.001), had higher education levels (47 vs. 21%; p < 0.001), and had higher income. Patients using OSG reported a higher share of metastatic disease (17 vs. 12%; p < 0.001). Patients using OSG reported greater distress. There were no significant differences in anxiety, depression, and global quality of life. In the face-to-face support groups, patient ratings were better for exchanging information, gaining recognition, and caring for others. Patients using OSG demanded a more active role in the treatment decision-making process (58 vs. 33%; p < 0.001) and changed their initial treatment decision more frequently (29 vs. 25%; p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Both modalities of peer support received very positive ratings by their users and have significant impact on treatment decision-making.

Implications for cancer survivors

Older patients might benefit more from the continuous social support in face-to-face support groups. OSG offer low-threshold advice for acute problems to younger and better educated patients with high distress.

Trial registration

www.germanctr.de, number DRKS00005086

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–76.

Andel GV, Bottomley A, Fosså SD, et al. An international field study of the EORTC QLQ-PR25: a questionnaire for assessing the health-related quality of life of patients with prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:2418–24.

Bender JL, Katz J, Ferris LE, et al. What is the role of online support from the perspective of facilitators of face-to-face support groups? A multi-method study of the use of breast cancer online communities. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93:472–9.

Bisson JI, Chubb HL, Bennett S, et al. The prevalence and predictors of psychological distress in patients with early localized prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2002;90:56–61.

Chewning B, Bylund CL, Shah B, et al. Patient preferences for shared decisions: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86:9–18.

Cocks K, King MT, Velikova G, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for interpreting change scores for the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:1713–21.

Davison KP, Pennebaker JW, Dickerson SS. Who talks? The social psychology of illness support groups. Am Psychol. 2000;55:205–17.

De Sousa A, Sonavane S, Mehta J. Psychological aspects of prostate cancer: a clinical review. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2012;15:120–7.

Deetjen U, Powell JA. Informational and emotional elements in online support groups: a Bayesian approach to large-scale content analysis. JAMIA. 2016;23:508–13.

Degner LF, Sloan JA, Venkatesh P. The Control Preferences Scale. Can J Nurs Res. 1997;29:21–43.

Feinberg I, Frijters J, Johnson-Lawrence V, et al. Examining associations between health information seeking behavior and adult education status in the U.S.: an analysis of the 2012 PIAAC Data. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0148751.

Galea S, Tracy M. Participation rates in epidemiologic studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:643–53.

Gottlieb BH, Wachala ED. Cancer support groups: a critical review of empirical studies. Psychooncology. 2007;16:379–400.

Grégoire I, Kalogeropoulos D, Corcos J. The effectiveness of a professionally led support group for men with prostate cancer. Urol Nurs. 1997;17:58–66.

Hinz A, Singer S, Brähler E. European reference values for the quality of life questionnaire EORTC QLQ-C30: results of a German investigation and a summarizing analysis of six European general population normative studies. Acta Oncol. 2014;53:958–65.

Huber J, Ihrig A, Peters T, et al. Decision-making in localized prostate cancer: lessons learned from an online support group. BJU Int. 2011;107:1570–5.

Huber J, Streuli JC, Lozankovski N, et al. The complex interplay of physician, patient, and spouse in preoperative counseling for radical prostatectomy: a comparative mixed-method analysis of 30 videotaped consultations. Psychooncology. 2016;25:949–56.

Huber J, Maatz P, Muck T, et al. The effect of an online support group on patients’ treatment decisions for localized prostate cancer: an online survey. Urol Oncol. 2017;35:37.e19–28.

Ihrig A, Keller M, Hartmann M, et al. Treatment decision-making in localized prostate cancer: why patients chose either radical prostatectomy or external beam radiation therapy. BJU Int. 2011;108:1274–8.

Klemm P, Hardie T. Depression in internet and face-to-face cancer support groups: a pilot study. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29:E45–51.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:613–21.

Löwe B, Wahl I, Rose M, et al. A 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2010;122:86–95.

National Comprehensive Cancer N. Distress management. Clinical practice guidelines. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2003;1:344–74.

Oliffe JL, Chambers S, Garrett B, et al. Prostate cancer support groups: Canada-based specialists’ perspectives. Am J Mens Health. 2015;9:163–72.

Perez MA, Skinner EC, Meyerowitz BE. Sexuality and intimacy following radical prostatectomy: patient and partner perspectives. Health Psychol. 2002;21:288–93.

Ramsey SD, Zeliadt SB, Arora NK, et al. Access to information sources and treatment considerations among men with local stage prostate cancer. Urology. 2009;74:509–15.

Resnick MJ, Lacchetti C, Bergman J, et al. Prostate cancer survivorship care guideline: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Endorsement. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1078–85.

Setoyama Y, Yamazaki Y, Nakayama K. Comparing support to breast cancer patients from online communities and face-to-face support groups. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85:e95–e100.

Sidana A, Hernandez DJ, Feng Z, et al. Treatment decision-making for localized prostate cancer: what younger men choose and why. Prostate. 2011;72:58–64.

Singh JA, Sloan JA, Atherton PJ, et al. Preferred roles in treatment decision making among patients with cancer: a pooled analysis of studies using the Control Preferences Scale. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16:688–96.

Stanton AL, Thompson EH, Crespi CM, et al. Project connect online: randomized trial of an internet-based program to chronicle the cancer experience and facilitate communication. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3411–7.

Treadgold CL, Kuperberg A. Been there, done that, wrote the blog: the choices and challenges of supporting adolescents and young adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4842–9.

Valero-Aguilera B, Bermúdez-Tamayo C, García-Gutiérrez JF, et al. Information needs and Internet use in urological and breast cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2013;22:545–52.

Van Gelder MMHJ, Bretveld RW, Roeleveld N. Web-based questionnaires: the future in epidemiology? Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:1292–8.

Van Uden-Kraan CF, Drossaert CHC, Taal E, et al. Participation in online patient support groups endorses patients’ empowerment. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74:61–9.

Wald HS, Dube CE, Anthony DC. Untangling the Web—the impact of Internet use on health care and the physician-patient relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;68:218–24.

Walsh MC, Trentham-Dietz A, Schroepfer TA, et al. Cancer information sources used by patients to inform and influence treatment decisions. J Health Commun. 2010;15:445–63.

White VM, Young M-A, Farrelly A, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a telephone-based peer-support program for women carrying a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation: impact on psychological distress. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:4073–80.

Xu Y, Testerman LS, Owen JE, et al. Modeling intention to participate in face-to-face and online lung cancer support groups. Psychooncology. 2014;23:555–61.

Acknowledgments

We thank the BPS and German Cancer Aid for endorsing our project. The Foundation of the Federal Bank of Baden-Wuerttemberg supported this study (grant 2012030055). Proof-Reading-Service.com Ltd. provided language assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Transparency declaration

The lead author affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Previous presentation

This study is presented in part at the Annual Meeting of the German Association of Urology, Düsseldorf, Germany, October 1–4, 2014; International Psycho-Oncology Society Congress, Lisbon, Portugal, October 20–24, 2014; Annual Meeting of the European Association of Urology, Madrid, Spain, March 20–24, 2015; and Annual Meeting of the American Association of Urology, New Orleans, LA, USA, May 15–19, 2015.

Funding

The study received financial support by the Foundation of the Federal Bank of Baden-Wuerttemberg (grant 2012030055).

Conflict of interest

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare no support from any organization for the submitted work, no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years, and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. Dr. Huber reports personal fees from Janssen and grants and non-financial support from Takeda, outside the submitted work. Dr. Keck reports advisory works and financial support (congresses) from Astellas, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, General Electric, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, and Sanofi, outside the submitted work. Mr. Enders is a member of the Prostate Cancer Patient Support Organization of Germany (BPS).

Ethical approval

The Ethics Committee of the University of Dresden approved our study protocol (EK 75032013). All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Key message

Prostate cancer patients visiting face-to-face and online peer support groups are very content with their modality and report significant impact on their treatment decision-making. Online users are younger, are better educated, have higher distress, and demand a more active role in treatment decisions. Face-to-face group users report more physical problems and benefit more from their visits.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PDF 147 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Huber, J., Muck, T., Maatz, P. et al. Face-to-face vs. online peer support groups for prostate cancer: A cross-sectional comparison study. J Cancer Surviv 12, 1–9 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-017-0633-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-017-0633-0