Abstract

Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) is a recently described method for detecting gross deletions or duplications of DNA sequences, aberrations which are commonly overlooked by standard diagnostic analysis. To determine the incidence of copy number variants in cancer predisposition genes from families in the Wessex region, we have analysed the hMLH1 and hMSH2 genes in patients with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), BRCA1 and BRCA2 in families with hereditary breast/ovarian cancer (BRCA) and APC in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis coli (FAP). Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (n=162) and FAP (n=74) probands were fully screened for small mutations, and cases for which no causative abnormality were found (HNPCC, n=122; FAP, n=24) were screened by MLPA. Complete or partial gene deletions were identified in seven cases for hMSH2 (5.7% of mutation-negative HNPCC; 4.3% of all HNPCC), no cases for hMLH1 and six cases for APC (25% of mutation negative FAP; 8% of all FAP). For BRCA1 and BRCA2, a partial mutation screen was performed and 136 mutation-negative cases were selected for MLPA. Five deletions and one duplication were found for BRCA1 (4.4% of mutation-negative BRCA cases) and one deletion for BRCA2 (0.7% of mutation-negative BRCA cases). Cost analysis indicates it is marginally more cost effective to perform MLPA prior to point mutation screening, but the main advantage gained by prescreening is a greatly reduced reporting time for the patients who are positive. These data demonstrate that dosage analysis is an essential component of genetic screening for cancer predisposition genes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) is a new, high-resolution method for detecting copy number variations in genomic sequences (Schouten et al, 2002). Available evidence suggests that MLPA is a robust assay, which offers several advantages over existing techniques (Taylor et al, 2003). Many diagnostic genetics laboratories are therefore adopting MLPA for analysis of genes such as hMLH1, hMSH2, BRCA1, BRCA2 and APC in preference to other techniques, for example, those based on quantitative-fluorescent PCR (QF-PCR) or multiple amplifiable probe hybridisation (MAPH). Laboratories have to decide whether dosage analysis should be performed before or after point mutation analysis, a decision that depends in part on the frequency of copy number variants in the local population.

Copy number variants in cancer predisposition genes are found at a frequency of around 4–15% in most countries, although founder effects have been reported in some study populations (Petrij-Bosch et al, 1997; Wagner et al, 2003). Previous studies of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) patients using QF-PCR or Southern blotting have detected hMLH1 and hMSH2 copy number variants in 5% of probands in Germany (Wang et al, 2003), 5% in Japan (Nakagawa et al, 2003), 15% in France (Charbonnier et al, 2002) and 27% in the USA (Wagner et al, 2003). Two analyses using MLPA have reported hMLH1 and hMSH2 copy number variants in 13% of families from Holland (Gille et al, 2002) and 6% from the North of England (Taylor et al, 2003). Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification studies of breast/ovarian cancer patients have given similar figures with 14% of Italian probands (Montagna et al, 2003) and 4% of Dutch probands (Hogervorst et al, 2003) having a dosage variant of the BRCA1 gene. One published study of familial adenomatous polyposis coli (FAP) patients using QF-PCR detected large deletions of APC in 12% of classical polyposis patients (Sieber et al, 2002).

With such a significant detection rate of copy number variants, it is clearly important to decide whether MLPA should be employed before or after standard mutation analysis. We present here an analysis of the frequency of copy number variants in HNPCC, FAP and hereditary breast/ovarian cancer from the Wessex region of the UK (which has a population of approximately 3 million people) and compare the relative testing cost and waiting times for prospective vs retrospective MLPA screening.

Materials and methods

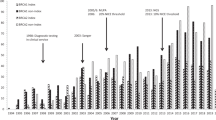

HNPCC cohort

During the 8-year period 1995–2003, a total of 162 probands referred for suspected HNPCC from the Wessex region were collected and screened for point mutations, microdeletions or microinsertions of the hMLH1 and hMSH2 genes using single-stranded conformation polymorphism (SSCP) heteroduplex analysis or, more recently, denaturing high-performance liquid chromotography (dHPLC) followed by direct sequencing of abnormal fragments. In all, 50 of these patients fulfilled the Amsterdam criteria for HNPCC, that is, three relatives with colorectal cancer (CRC), one of whom is a first-degree relative of the other two; CRC involving at least two generations; one or more CRC cases diagnosed before the age of 50 years. A causative mutation, that is, a premature stop codon, frameshift, splice recognition site change or amino-acid change that is known to compromise function, was found in a total of 40 patients (24.7%), of whom 24 fulfilled the stringent Amsterdam criteria (48% of Amsterdam-positive patients) and 16 were patients who fulfilled one or more of the less stringent Bethesda Criteria (14% of patients not fulfilling the Amsterdam Criteria). The 122 patients in whom no mutation had been found were subsequently analysed by MLPA.

Hereditary breast/ovarian cancer cohort

Over the 6-year period 1997–2003, we performed a partial BRCA1 and BRCA2 screen on 679 probands. All patients were tested using the protein truncation test (PTT) to look for frameshift or nonsense mutations in exon 11 of both BRCA1 and BRCA2 and by SSCP or dHPLC followed by sequencing of aberrant fragments for BRCA1 exons 2 and 20 plus BRCA2 exon 10. This partial screen covers approximately 65 and 55% of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 coding sequences, respectively, and a causative mutation was found in 99 patients (15%). All pedigrees were reviewed and ranked in order of likelihood for an underlying BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation using the recently developed Manchester scoring system (Evans et al, 2004). In brief, each breast or ovarian cancer scores according to the age at onset and cancer site (ovarian cancer scores higher than breast cancer), with a small additional score for prostate and pancreatic cancers in BRCA2. A score of 10 or more equates to at least a 15% chance of a mutation being detected, the higher the crude score, the higher the likelihood. In all, 259 samples scoring 10 or above had been partly or wholly analysed in our laboratory previously and 83 mutations had been detected (32%). In order to assess the usefulness of BRCA1 and BRCA2 MLPA, we analysed 136 cases selected from this group where DNA was available for further analysis and in which no mutation had been found in the previous screen.

FAP cohort

During the 11-year period 1992–2003, a total of 74 FAP probands from the Wessex region were collected and screened for point mutations, microdeletions or microinsertions of the APC gene using SSCP or dHPLC followed by direct sequencing of abnormal fragments. A causative mutation was found in a total of 50 patients (68%). The 24 patients in whom no mutation had been found were subsequently analysed by MLPA.

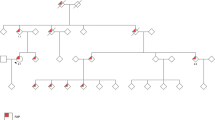

Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification

Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification analysis was performed using kits from MRC-Holland (Amsterdam, The Netherlands). The kits include probes for each exon of the gene in question (except BRCA2 exons 5, 6, 23 and 26), probes for a number of control regions across the genome, plus further controls to check for adequate quality of test DNA and efficient ligation. The only alteration to the manufacturer's protocol was that 1 μl of DNA was used per MLPA reaction (typically 400–600 ng) rather than the suggested 100 ng of DNA. Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification PCR products were separated on an ABI3100 genetic analyser and interpreted using Genotyper version 2.0. Peak heights from each patient were then exported to an Excel spreadsheet, which was designed to assess the ratios of each test peak relative to all other peaks for that individual. Ratios of test peaks to control peaks and control peaks to other control peaks in each patient sample were compared to the same ratios obtained for two normal individuals, which were included in each run. For normal sequences, a dosage quotient of 1.0 is expected; if a deletion or duplication is present, the dosage quotient should be 0.5 and 1.5, respectively. In a series of control experiments, we found that normal sequences gave a mean dosage quotient of 1.04 (range 0.79–1.27, standard deviation=0.06, n=143), deleted sequences gave a mean dosage quotient of 0.50 (range 0.34–0.67, standard deviation=0.07, n=110) and duplicated sequences gave a mean dosage quotient of 1.60 (range 1.32–1.73, standard deviation=0.06, n=60). Results were deemed acceptable if the dosage quotient for each control peak fell within the range 0.8–1.2. A deletion was scored if the mean dosage quotient of the test to internal control peaks was less than 0.7, and a duplication was scored if the mean dosage quotient was 1.3 or greater. Intermediate results were discounted and samples were repeated if the scores did not fall into the above three categories. In all cases (approximately 5% of samples), we were able to obtain a satisfactory result on repeat analysis sometimes by reducing or increasing the amount of input DNA. Deletions of multiple contiguous exons are extremely unlikely to have arisen as false positives by chance in the MLPA assay (Taylor et al, 2003), and thus we did not confirm these independently. Apparent deletions of a single exon, however, do need confirmation (Taylor et al, 2003) and so we first checked the sequence of the exon in question to see if a point mutation or microdeletion/microinsertion was present that might interfere with MLPA probe hybridisation. If the sequence was normal, the deletion was confirmed by MAPH or QF-PCR. In this series, we did not observe any false-positive results, that is, all single-exon abnormalities detected by MLPA turned out to be real copy number changes or due to exonic mutations. A typical MLPA result is shown in Figure 1.

dHPLC and PTT analysis

PCR products were run on a WAV-3500 Transgenomic WAVE™ machine with Navigator v1.5. 2 software and WAVE Optimized™ Buffers (Transgenomic Inc., Crewe, UK). PCR product (8 μl) was injected at column temperatures selected using the Navigator melting algorithm software. In general, PCR primers (sequences available on request) were chosen to include at least 40–50 bp of flanking intron sequence for each exon. Protein truncation test analysis was performed using the standard method and primer sequences published by Plummer et al (1995).

Sequencing analysis

Relevant PCR products were sequenced in both forward and reverse directions using BigDye® Terminator v1.1. or v3.1 chemistry (Applied Biosystems). Samples underwent 25 cycles of amplification (30 s at 96°C, 15 s at 50°C and 2 min at 60°C). Excess terminators were removed using DyeEx™ 2.0 spin columns (Qiagen) prior to running on an ABI 3100 genetic analyser.

Costings

Reagent cost calculations (rounded to the nearest pound) were calculated per sample and are based on standard operational procedures employed at the Wessex Regional Genetics Laboratory, average referral rates per annum, average detection rates per gene and reagent list prices as at December 2003. Reagent costs for hMLH1 and hMSH2 (full mutation screen and sequence confirmation)=£56; BRCA1/2 (PTT plus full mutation screen and sequence confirmation) £116; APC (full mutation screen and sequence confirmation)=£62; and MLPA=£7.

To calculate staff costs, we have used an approximate wage estimate of £10 h−1 (equivalent to an annual wage of £19 500) and an average hands-on time of 2 h for MLPA, 13 h for PTT plus the limited BRCA1/2 screen, 52.5 h for dHPLC analysis plus sequencing for HNPCC, an estimated 39 h for dHPLC analysis plus sequencing for a full BRCA1/2 screen and 30 h for dHPLC analysis plus sequencing for FAP. Reporting time calculations were based on a mean reporting time of 5 days for MLPA, 50 days for PTT and 90 days for dHPLC plus sequencing.

Results

Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer

Using MLPA, we found a deletion of one or more exons of the hMSH2 gene in seven of the 122 HNPCC patients in whom no causative mutation had been detected previously (see Table 1). This equates to 4.3% of all HNPCC probands or 5.7% of probands without a known causative mutation. Four of these mutations were found in Amsterdam-positive patients (8% of all Amsterdam-positive patients; 3.3% of previously mutation-negative probands) and three were Amsterdam-negative patients (2.7% of all Amsterdam-negative patients; 2.5% of previously mutation-negative probands). One patient had a deletion of just exon 1 of the hMSH2 gene and this was confirmed by a separate laboratory using MAPH (data not shown). No copy number changes were detected in the hMLH1 gene.

Breast/ovarian cancer

Of the 136 patients analysed, six copy number variants were found within the BRCA1 gene and one copy number variant was found for BRCA2 (5.1%. of cases that were tested and were negative in the partial mutation screen). The mutations are listed in Table 1. The individual (BRCA1 #1) with a deletion of BRCA1 exon 20 only was confirmed in another laboratory using QF-PCR (data not shown); all the other deletions or duplications involved contiguous exons. In addition to these cases, MLPA detected apparent single-exon deletions in two breast cancer patients who were subsequently shown to have microdeletions within the MLPA probe recognition sequences: 364delT in BRCA1 exon 6 and 983delACAG in BRCA2 exon 9. These microdeletions prevented the efficient ligation of the MLPA probes, resulting in an apparent deletion of the whole exon. Since these mutations would have been picked up by the full mutation screens that are currently being implemented by NHS diagnostic laboratories, we did not score them as additional MLPA-detectable pathogenetic lesions in our analysis.

FAP patients

Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification analysis of the 24 previously mutation-negative patients detected a gross deletion in six individuals (see Table 1), equating to 8% of all patients or 25% of patients in whom no mutation had previously been found.

Costings

The calculations of reagent costs and staff wages are shown in Table 2 for the different scenarios depending upon sample category and the initial mutation detection method of choice. Overheads, equipment costs and depreciation are not included. All calculations are based on our current annual referral rate for each syndrome (HNPCC, n=24; breast cancer, n=94; FAP, n=7). The final estimated costs are not simply the sum of the component tests due to the sequential nature of the analysis, for example, if MLPA is performed as a prescreen then those individuals who are positive will not be subject to the full mutation screen. Similarly, BRCA patients for whom mutations were identified by PTT would not be subject to further analysis, except for sequence confirmation.

For HNPCC, prescreening with MLPA results in a saving of £17 per sample for all referrals (£35 for Amsterdam-positive patients). This equates to a total financial saving per year of £408, if MLPA is the first mutation detection method used. For breast cancer patients, MLPA prescreening results in a saving of £22 per patient, a total of £2016 per year. For FAP, a saving of £6 per person can be made, a total of £49 per year.

Reporting times

A comparison of the average reporting times (see Table 2) shows that a saving of 3 days can be obtained by prescreening all HNPCC referrals with MLPA, increasing to 5 days if testing Amsterdam-positive patients only. Although 3–6 days appears to be a minimal saving overall, each patient with an MLPA-detectable abnormality would be reported within 7 days, 81–116 days earlier than the average reporting time (Table 2). For breast cancer patients, an average of 6 days can be saved by prescreening with MLPA, and for FAP patients this figure is 3 days.

Discussion

Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification has rapidly gained acceptance in genetic diagnostic laboratories due to its simplicity, relatively low cost, capacity for reasonably high throughput and robustness (Di Fiore et al, 2004). Using MLPA, we have identified copy number variants at a frequency of 5–8% in cancer predisposition genes from families in the Wessex region. Although this is a relatively small proportion of all cases, it does represent a significant increase in the number of families for whom a causative mutation can be identified, and thus an increased number of individuals who will benefit from appropriate counselling and management. In our series, standard point mutation analysis enabled causative mutations to be identified in 25% of HNPCC families, 32% of BRCA families (partial mutation screen only) with a Manchester score of ⩾10 and 68% of FAP families. With the incorporation of MLPA in addition to point mutation screening, causative mutations were identified in 29% of HNPCC families, 37% of high-risk breast cancer families and 76% of FAP families.

Considering the nature of the copy number variants, we identified some features that deserve comment. First, for HNPCC we found seven copy number variants for hMSH2 but none for hMLH1. This is in contrast to another study from the UK in which copy number variants were seen in both genes, although the overall frequency of variants was similar in both studies (Taylor et al, 2003). Second, copy number variants were more common for BRCA1 (n=6) compared to BRCA2 (n=1). Finally, four of six APC variants in apparently unrelated individuals involved the loss of the whole gene. Although we have not shown that these abnormalities are the same at the molecular level, they may be indicative of a local founder effect.

As expected, the proportion of HNPCC copy number variants was higher in individuals who were Amsterdam positive (8%) compared to those who were Amsterdam negative (2.7%). One unexpected benefit from this study was the detection of two small mutations at the probe binding sites (1 and 4 bp deletions) by MLPA. Although we did not score these changes as new MLPA-detectable pathogenetic lesions in our analysis, these results demonstrate that MLPA may be used to detect small mutations in addition to gross copy number changes.

The cost calculations presented here show that a modest total financial saving of around £2500 per year may be obtained by choosing MLPA as the initial mutation screening method for all hereditary cancer referrals (for a region with a population of 3 million people), as well as the additional advantage of quicker reporting times for positive individuals. The number of individuals who would benefit from the shorter reporting time equates to approximately 150–200 cases per annum in the UK.

Overall our data highlight the fact that dosage analysis is an essential tool in cancer diagnostics that should be undertaken by all laboratories, that screen for mutations in cancer predisposition genes. We have also shown that it is more appropriate to perform MLPA analysis prior to, rather than after, point mutation analysis and that reporting times can be substantially reduced for a proportion of affected individuals.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Charbonnier F, Olschwang S, Wang Q, Boisson C, Martin C, Buisine MP, Puisieux A, Frebourg T (2002) MSH2 in contrast to MLH1 and MSH6 is frequently inactivated by exonic and promoter rearrangements in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Cancer Res 62: 848–853

Di Fiore F, Charbonnier F, Martin C, Frerot S, Olschwang S, Wang Q, Boisson C, Buisine M-P, Nilbert M, Lindblom A, Frebourg T (2004) Screening for genomic rearrangements of the MMR genes must be included in the routine diagnosis of HNPCC. J Med Genet 41: 18–20

Evans G, Eccles DM, Rahman N, Young K, Bulman M, Amir E, Shenton A, Howell A, Lalloo F (2004) A new scoring system for the chances of identifying a BRCA1/2 mutation, outperforms existing models including BRCAPRO. J Med Genet 41: 474–480

Gille JJ, Hogervorst FB, Pals G, Wijnen JT, van Schooten RJ, Dommering CJ, Meijer GA, Craanen ME, Nederlof PM, de Jong D, McElgunn CJ, Schouten JP, Menko FH (2002) Genomic deletions of MSH2 and MLH1 in colorectal cancer families detected by a novel mutation detection approach. Br J Cancer 87: 892–897

Hogervorst FB, Nederlof PM, Gille JJ, McElgunn CJ, Grippeling M, Pruntel R, Regnerus R, van Welsem T, van Spaendonk R, Menko FH, Klujit I, Dommering C, Verhoef S, Schouten JP, van't Veer LJ, Pals G (2003) Large genomic deletions and duplications in the BRCA1 gene identified by a novel quantitative method. Cancer Res 63: 1449–1453

Montagna M, Palma MD, Menin C, Agata S, De Nicolo A, Chieco-Bianchi L, D'Andrea E (2003) Genomic rearrangements account for more than one-third of the BRCA1 mutations in northern Italian breast/ovarian cancer families. Hum Mol Genet 12: 1055–1061

Nakagawa H, Hampel H, de la Chapelle A (2003) Identification and characterisation of genomic rearrangements of MSH2 and MLH1 in Lynch syndrome (HNPCC) by novel techniques. Hum Mutat 22: 258

Petrij-Bosch A, Peelen T, van Vliet M, van Eijk R, Olmer R, Drusedau M, Hogervorst FB, Hageman S, Arts PJ, Ligtenberg MJ, Meijers-Heijboer H, Klijn JG, Vasen HF, Cornelisse CJ, van't Veer LJ, Bakker E, van Ommen GJ, Devilee P (1997) BRCA1 genomic deletions are major founder mutations in Dutch breast cancer patients. Nat Genet 17: 341–345

Plummer SJ, Anton-Culver H, Webster L, Noble B, Liao S, Kennedy A, Belinson J, Casey G (1995) Detection of BRCA1 mutations by the protein truncation test. Hum Mol Genet 4: 1989–1991

Schouten JP, McElgunn CJ, Waaijer R, Zwijnenburg D, Diepvens F, Pals G (2002) Relative quantification of 40 nucleic acid sequences by multiplex ligation-dependant probe amplification. Nucleic Acid Res 30: e57

Sieber OM, Lamlum H, Crabtree MD, Rowan AJ, Barclay E, Lipton L, Hodgson S, Thomas HJ, Neale K, Phillips RK, Farrington SM, Dunlop MG, Mueller HJ, Bisgaard ML, Bulow S, Fidalgo P, Albuquerque C, Scarano MI, Bodmer W, Tomlinson IP, Heinimann K (2002) Whole-gene APC deletions cause classical familial adenomatous polyposis, but not attenuated polyposis or ‘multiple’ colorectal adenomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 2954–2958

Taylor F, Charlton RS, Burn J, Sheridan E, Taylor GR (2003) Genomic deletions in MSH2 or MLH1 are a frequent cause of hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer: identification of novel and recurrent deletions by MLPA. Hum Mutat 22: 428–433

Wagner A, Barrows A, Wijnen JT, van der Klift H, Franken PF, Verkuijlen P, Nakagawa H, Geugien M, Jaghmohan-Changur S, Breukel C, Meijers-Heijboer H, Morreau H, van Puijenbroek M, Burn J, Coronel S, Kinarski Y, Okimoto R, Watson P, Lynch JF, de la Chapelle A, Lynch HT, Fodde R (2003) Molecular analysis of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer in the United States: high mutation detection rate among clinically selected families and characterisation of an American founder genomic deletion of the MSH2 gene. Am J Hum Genet 72: 1088–1100

Wang Y, Friedl W, Lamberti C, Jungck M, Mathiak M, Pagenstecher C, Propping P, Mangold E (2003) Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer: frequent occurrence of large genomic deletions in MSH2 and MLH1 genes. Int J Cancer 103: 636–641

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr John Armour (Institute of Genetics, University of Nottingham) for MAPH confirmation of the hMSH2 exon 1 deletion case and Dr Catherine Roberts (Northern Molecular Genetics Diagnostic Service, Newcastle) for QF-PCR confirmation of the BRCA1 exon 20 deletion case.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Bunyan, D., Eccles, D., Sillibourne, J. et al. Dosage analysis of cancer predisposition genes by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. Br J Cancer 91, 1155–1159 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602121

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602121

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Early Gastric Cancer: identification of molecular markers able to distinguish submucosa-penetrating lesions with different prognosis

Gastric Cancer (2021)

-

KRAS status is related to histological phenotype in gastric cancer: results from a large multicentre study

Gastric Cancer (2019)

-

First description of mutational analysis of MLH1, MSH2 and MSH6 in Algerian families with suspected Lynch syndrome

Familial Cancer (2017)

-

Copy number of the Adenomatous Polyposis Coli gene is not always neutral in sporadic colorectal cancers with loss of heterozygosity for the gene

BMC Cancer (2016)

-

Relationship of immunohistochemistry, copy number aberrations and epigenetic disorders with BRCAness pattern in hereditary and sporadic breast cancer

Familial Cancer (2016)