Key Points

-

Peutz–Jeghers syndrome (PJS) is an autosomal polyposis disorder that is characterized by cancer predisposition at a young age. It is associated with inactivating mutations in the LKB1 gene.

-

Different hamartomatous polyposis syndromes are associated with different types of genetic defects. PJS is characterized by gastrointestinal hamartomas that have a smooth-muscle core.

-

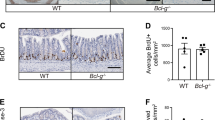

LKB1 is required for normal fetal development and is present in apoptotic intestinal cells. LKB1 has been shown to be involved in p53-mediated apoptosis. LKB1 phosphorylates p53 at low levels, which might be required for p53 activation.

-

LKB1 has also been shown to control cell proliferation. It interacts with the chromatin remodelling protein brahma-related gene-1 (BRG1), and also with the cell-cycle regulatory proteins LKB1-interacting protein 1 (LIP1) and WAF1.

-

LKB1 is therefore an important tumour suppressor that might be developed as a cancer therapeutic target.

Abstract

Peutz–Jeghers syndrome (PJS) is a rare, inherited intestinal polyposis syndrome that is associated with a significantly increased risk of several types of cancer — particularly those of the gastrointestinal and reproductive systems. Most cases of PJS have been associated with loss-of-function mutations in the ubiquitously expressed LKB1 gene, which encodes a serine/ threonine kinase. Recent studies have begun to illustrate the molecular mechanisms by which LKB1 functions as an important new tumour suppressor.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Coit, D. G. in Cancer: Principles & Practice of Oncology (eds DeVita, V. T., Hellman, S. & Rosenberg, S. A.) 1204–1216 (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2001).

Peutz, J. D. A. Over een zeer Merkwaardige, gecombinerde familiare polyposis van de slijmvliezen van den tractus intestinalis met die van de neuskeelholte en gepaard met elgenaardige pigmentaties van huid en slijmvlisen. Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd. 10, 134 (1921).

Jeghers, H., McKusick, V. A. & Katz, K. H. Generalized intestinal polyposis and melanin spots of the oral mucosa, lips and digits. N. Engl. J. Med. 241, 993–1005 (1949).

Bartholomew, L. G., Dahlin, D. C. & Waugh, J. M. Intestinal polyposis associated with mucocutaneous melanin pigmentation (Peutz–Jeghers syndrome). Gastroenterology 32, 434–451 (1957).

Bartholomew, L. G., Moore, C. E., Dahlin, D. C. & Waugh, J. M. Intestinal polyposis associated with mucocutaneous pigmentation. Surg. Gyn. Obstet. 115, 1–11 (1962).

Hemminki, A. et al. A serine/threonine kinase gene defective in Peutz–Jeghers syndrome. Nature 391, 184–187 (1998).One of the first papers that identifies inactivating mutations in LKB1 as the molecular basis for Peutz–Jeghers syndrome.

Jenne, D. E. et al. Peutz–Jeghers syndrome is caused by mutations in a novel serine threonine kinase. Nature Genet. 18, 38–43 (1998).One of the first papers that identifies inactivating mutations in LKB1 as the molecular basis for Peutz–Jeghers syndrome, and describes expression patterns in human fetuses and adults.

Olschwang, S., Boisson, C. & Thomas, G. Peutz–Jeghers families unlinked to STK11/LKB1 gene mutations are highly predisposed to primitive biliary adenocarcinoma. J. Med. Genet. 38, 356–360 (2001).

Hemminki, A. et al. Localization of a susceptibility locus for Peutz–Jeghers syndrome to 19p using comparative genomic hybridization and targeted linkage analysis. Nature Genet. 15, 87–90 (1997).

McAllister, A. J. & Richards, K. F. Peutz–Jeghers syndrome: experience with twenty patients in five generations. Am. J. Surg. 134, 717–720 (1977).

Mehenni, H. et al. Peutz–Jeghers syndrome: confirmation of linkage to chromosome 19p13.3 and identification of a potential second locus, on 19q13.4. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 61, 1327–1334 (1997).

Giardiello, F. M. et al. Very high risk of cancer in familial Peutz–Jeghers syndrome. Gastroenterology 119, 1447–1453 (2000).A statistical analysis of data from published reports on incidence of cancer in patients with Peutz–Jeghers syndrome, showing greatly increased risk for several types of cancer.

Boardman, L. A. et al. Increased risk for cancer in patients with the Peutz–Jeghers syndrome. Ann. Intern. Med. 128, 896–899 (1998).

Giardiello, F. M. et al. Increased risk of cancer in the Peutz–Jeghers syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 316, 1511–1514 (1987).

Spigelman, A. D., Murday, V. & Phillips, R. K. Cancer and the Peutz–Jeghers syndrome. Gut 30, 1588–1590 (1989).

Entius, M. M. et al. Molecular genetic alterations in hamartomatous polyps and carcinomas of patients with Peutz–Jeghers syndrome. J. Clin. Pathol. 54, 126–131 (2001).

Gruber, S. B. et al. Pathogenesis of adenocarcinoma in Peutz–Jeghers syndrome. Cancer Res. 58, 5267–5270 (1998).

Jiang, C. Y. et al. STK11/LKB1 germline mutations are not identified in most Peutz–Jeghers syndrome patients. Clin. Genet. 56, 136–141 (1999).

Miyaki, M. et al. Somatic mutations of LKB1 and β-catenin genes in gastrointestinal polyps from patients with Peutz–Jeghers syndrome. Cancer Res. 60, 6311–6313 (2000).

Miyoshi, H. et al. Gastrointestinal hamartomatous polyposis in lkb1 heterozygous knockout mice. Cancer Res. 62, 2261–2266 (2002).The first publication that describes the gastrointestinal polyposis that is similar to Peutz–Jeghers syndrome, which occurs in Lkb1+/− mice. No evidence of LOH was found in the polyps, indicating that haploinsufficiency of Lkb1 can cause polyposis.

Howe, J. R. et al. Mutations in the SMAD4/DPC4 gene in juvenile polyposis. Science 280, 1086–1088 (1998).

Takaku, K. et al. Gastric and duodenal polyps in Smad4 (Dpc4) knockout mice. Cancer Res. 59, 6113–6117 (1999).

Howe, J. R. et al. Germline mutations of the gene encoding bone morphogenetic protein receptor 1A in juvenile polyposis. Nature Genet. 28, 184–187 (2001).

Wirtzfeld, D. A., Petrelli, N. J. & Rodriguez-Bigas, M. A. Hamartomatous polyposis syndromes: molecular genetics, neoplastic risk, and surveillance recommendations. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 8, 319–327 (2001).

Xu, X. et al. Haploid loss of the tumor suppressor Smad4/Dpc4 initiates gastric polyposis and cancer in mice. Oncogene 19, 1868–1874 (2000).

Jacoby, R. F. et al. A juvenile polyposis tumor suppressor locus at 10q22 is deleted from nonepithelial cells in the lamina propria. Gastroenterology 112, 1398–1403 (1997).

Kinzler, K. W. & Vogelstein, B. Landscaping the cancer terrain. Science 280, 1036–1037 (1998).A proposal that polyps, such as in the case with juvenile polyposis syndrome, can be generated not as a result of mutations in the epithelial cells, but as a result of mutations in the stromal-cell population — a 'landscaping defect'.

Woodford-Richens, K. et al. Allelic loss at SMAD4 in polyps from juvenile polyposis patients and use of fluorescence in situ hybridization to demonstrate clonal origin of the epithelium. Cancer Res. 60, 2477–2482 (2000).

Wang, Z. J. et al. Allelic imbalance at the LKB1 (STK11) locus in tumours from patients with Peutz–Jeghers' syndrome provides evidence for a hamartoma- (adenoma)-carcinoma sequence. J. Pathol. 188, 9–13 (1999).Evidence that LOH of LKB1 occurs in the epithelial cells of PJS polyps, and an example of a hamartoma with adenomatous and carcinomatous lesions due to loss of LKB1 , indicating possible progression from hamartomas to cancer.

Day, D. W. The adenoma-carcinoma sequence. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 104 (Suppl.), 99–107 (1984).

Su, J. Y., Erikson, E. & Maller, J. L. Cloning and characterization of a novel serine/threonine protein kinase expressed in early Xenopus embryos. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 14430–14437 (1996).

Kemphues, K. J., Priess, J. R., Morton, D. G. & Cheng, N. S. Identification of genes required for cytoplasmic localization in early C. elegans embryos. Cell 52, 311–320 (1988).

Collins, S. P., Reoma, J. L., Gamm, D. M. & Uhler, M. D. LKB1, a novel serine/threonine protein kinase and potential tumour suppressor, is phosphorylated by cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) and prenylated in vivo. Biochem J. 345, 673–680 (2000).

Karuman, P. et al. The Peutz–Jegher gene product LKB1 is a mediator of p53-dependent cell death. Mol. Cell 7, 1307–1319 (2001).Shows elevated LKB1 expression in dying intestinal epithelial cells, and indicates a role for LKB1 in apoptosis in cultured cells and in the intestine. p53 is shown to be a crucial mediator of LKB1-induced apoptosis.

Nezu, J., Oku, A. & Shimane, M. Loss of cytoplasmic retention ability of mutant LKB1 found in Peutz–Jeghers syndrome patients. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 261, 750–755 (1999).

Smith, D. P., Spicer, J., Smith, A., Swift, S. & Ashworth, A. The mouse Peutz–Jeghers syndrome gene Lkb1 encodes a nuclear protein kinase. Hum. Mol. Genet. 8, 1479–1485 (1999).

Sapkota, G. P. et al. Identification and characterization of four novel phosphorylation sites (Ser31, Ser325, Thr336 and Thr366) on LKB1/STK11, the protein kinase mutated in Peutz–Jeghers cancer syndrome. Biochem. J. 362, 481–490 (2002).

Sapkota, G. P. et al. Phosphorylation of the protein kinase mutated in Peutz–Jeghers cancer syndrome, LKB1/STK11, at Ser431 by p90(RSK) and cAMP-dependent protein kinase, but not its farnesylation at Cys(433), is essential for LKB1 to suppress cell growth. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 19469–19482 (2001).Evidence that overexpressed LKB1 is phosphorylated by RSK and PKA in EGF- and forskolin-stimulated cells, respectively, and that LKB1 is farnesylated. Phosphorylation or farnesylation of LKB1 might be crucial for its growth-suppressive activity.

Wang, Z. J. et al. Germline mutations of the LKB1 (STK11) gene in Peutz–Jeghers patients. J. Med. Genet. 36, 365–368 (1999).

Young, R. H., Welch, W. R., Dickersin, G. R. & Scully, R. E. Ovarian sex cord tumor with annular tubules: review of 74 cases including 27 with Peutz–Jeghers syndrome and four with adenoma malignum of the cervix. Cancer 50, 1384–1402 (1982).

Rowan, A. et al. In situ analysis of LKB1/STK11 mRNA expression in human normal tissues and tumours. J. Pathol. 192, 203–206 (2000).

Potten, C. S. Stem cells in gastrointestinal epithelium: numbers, characteristics and death. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 353, 821–830 (1998).

Ylikorkala, A. et al. Vascular abnormalities and deregulation of VEGF in Lkb1-deficient mice. Science 293, 1323–1326 (2001).First paper describing the Lkb1−/− embryonic-lethal phenotype. Lkb1−/− embryos showed dysregulation of VEGF expression and decreased vascularization.

Liaw, D. et al. Germline mutations of the PTEN gene in Cowden disease, an inherited breast and thyroid cancer syndrome. Nature Genet. 16, 64–67 (1997).

Luukko, K., Ylikorkala, A., Tiainen, M. & Makela, T. P. Expression of LKB1 and PTEN tumor suppressor genes during mouse embryonic development. Mech. Dev. 83, 187–190 (1999).

Fenlon, J. W. Case report with angiographic evaluation. Radiology 103, 595–596 (1972).

Clarke, A. R., Gledhill, S., Hooper, M. L., Bird, C. C. & Wyllie, A. H. p53 dependence of early apoptotic and proliferative responses within the mouse intestinal epithelium following γ-irradiation. Oncogene 9, 1767–1773 (1994).

Merritt, A. J. et al. The role of p53 in spontaneous and radiation-induced apoptosis in the gastrointestinal tract of normal and p53-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 54, 614–617 (1994).

Tiainen, M., Ylikorkala, A. & Makela, T. P. Growth suppression by Lkb1 is mediated by a G(1) cell cycle arrest. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 9248–9251 (1999).First paper showing that LKB1 , when overexpressed, can induce cell-cycle arrest in certain types of cell line.

Furnari, F. B., Lin, H., Huang, H. S. & Cavenee, W. K. Growth suppression of glioma cells by PTEN requires a functional phosphatase catalytic domain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 94, 12479–12484 (1997).

Tiainen, M., Vaahtomeri, K., Ylikorkala, A. & Makela, T. P. Growth arrest by the LKB1 tumor suppressor: induction of p21(WAF1/CIP1). Hum. Mol. Genet. 11, 1497–1504 (2002).

Marignani, P. A., Kanai, F. & Carpenter, C. L. LKB1 associates with Brg1 and is necessary for Brg1-induced growth arrest. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 32415–32418 (2001).

Dunaief, J. L. et al. The retinoblastoma protein and BRG1 form a complex and cooperate to induce cell cycle arrest. Cell 79, 119–130 (1994).

Smith, D. P. et al. LIP1, a cytoplasmic protein functionally linked to the Peutz–Jeghers syndrome kinase LKB1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10, 2869–2877 (2001).

Acknowledgements

J. Y. and D. C. C are supported in part by National Cancer Institute grants. L. I. Y. is supported by a fellowship from the American Cancer Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Related links

Related links

DATABASES

Cancer.gov

LocusLink

Medscape DrugInfo

OMIM

FURTHER INFORMATION

The Network for Peutz Jeghers and Juvenile Polyposis Syndrome

Glossary

- HAMARTOMA

-

A benign overgrowth of tissue that is composed of cells that are normally present at that site. In the gastrointestinal tract, hamartomas typically have a marked expansion of the muscular and fibrous tissue layer.

- LOSS OF HETEROZYGOSITY

-

(LOH). In cells that carry a mutated allele of a tumour-suppressor gene, the gene becomes fully inactivated when the cell loses a large part of the chromosome that carries the wild-type allele. Regions with high frequency of LOH are believed to harbour tumour-suppressor genes.

- FLUORESCENT IN SITU HYBRIDIZATION

-

(FISH). A technique that is used to detect nucleic acids in cells or tissues by using probes that are coupled to a fluorescent dye.

- NON-CELL AUTONOMOUS

-

Describes a signal that is is passed from one cell to another.

- PRENYLATION

-

The covalent attachment of a hydrophobic prenyl group to a molecule. This can result in membrane localization.

- PYKNOTIC

-

Describes a condensed, misshapen nucleus, that is characteristic of an apoptotic cell.

- DOMINANT-NEGATIVE MUTANT

-

A non-functional mutant protein that competes with the normal, non-mutated protein, blocking its activity.

- FORSKOLIN

-

A vasodilating drug that is produced by the Coleus forskohlii plant. It activates adenylate cyclase, leading to elevated cyclic AMP levels.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yoo, L., Chung, D. & Yuan, J. LKB1 — A master tumour suppressor of the small intestine and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer 2, 529–535 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc843

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc843

This article is cited by

-

A pan-cancer analysis of driver gene mutations, DNA methylation and gene expressions reveals that chromatin remodeling is a major mechanism inducing global changes in cancer epigenomes

BMC Medical Genomics (2018)

-

An exploration of genotype-phenotype link between Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and STK11: a review

Familial Cancer (2018)

-

Characterization of the STK11 splicing variant as a normal splicing isomer in a patient with Peutz–Jeghers syndrome harboring genomic deletion of the STK11 gene

Human Genome Variation (2016)

-

AMPK and HIF signaling pathways regulate both longevity and cancer growth: the good news and the bad news about survival mechanisms

Biogerontology (2016)

-

Two variants in STK11 gene in Chinese patients with Peutz–Jeghers syndrome

Journal of Genetics (2012)