Abstract

Infantile spasms (ISS) are an epilepsy disorder frequently associated with severe developmental outcome and have diverse genetic etiologies. We ascertained 11 subjects with ISS and novel copy number variants (CNVs) and combined these with a new cohort with deletion 1p36 and ISS, and additional published patients with ISS and other chromosomal abnormalities. Using bioinformatics tools, we analyzed the gene content of these CNVs for enrichment in pathways of pathogenesis. Several important findings emerged. First, the gene content was enriched for the gene regulatory network involved in ventral forebrain development. Second, genes in pathways of synaptic function were overrepresented, significantly those involved in synaptic vesicle transport. Evidence also suggested roles for GABAergic synapses and the postsynaptic density. Third, we confirm the association of ISS with duplication of 14q12 and maternally inherited duplication of 15q11q13, and report the association with duplication of 21q21. We also present a patient with ISS and deletion 7q11.3 not involving MAGI2. Finally, we provide evidence that ISS in deletion 1p36 may be associated with deletion of KLHL17 and expand the epilepsy phenotype in that syndrome to include early infantile epileptic encephalopathy. Several of the identified pathways share functional links, and abnormalities of forebrain synaptic growth and function may form a common biologic mechanism underlying both ISS and autism. This study demonstrates a novel approach to the study of gene content in subjects with ISS and copy number variation, and contributes further evidence to support specific pathways of pathogenesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infantile spasms (ISS) are characterized by clusters of epileptic spasms usually before the age of 1 year and are often associated with an electrodecrement and hypsarrhythmia on electroencephalogram (EEG).1 Children with ISS tend to have poor developmental outcome, with an increased prevalence of autism.2 The increasing number of new single genes associated with ISS, including ARX, CDKL5, FOXG1, GRIN1, GRIN2A, MAGI2, MEF2C, SLC25A22, SPTAN1, and STXBP1, suggests diverse genetic causes.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 Many of these genes were identified from copy number variants (CNVs) or constitutional chromosomal rearrangements, suggesting that further study will lead to discovery of new ISS-associated genes.

Our initial review shows many of the ISS-associated genes cluster in two specific biological pathways: ventral forebrain development and forebrain synapse function. Abnormalities in ventral inhibitory GABAergic interneurons are implicated by the involvement of ARX and FOXG1, as both are transcription factors important in ventral forebrain development.15, 16 MEF2C may be a downstream transcriptional target of ARX and is differentially expressed in the forebrain in a mouse model of ISS with loss of Arx.17 Disturbance of the gene regulatory network involved in the development of the ventral forebrain, including GABAergic interneurons, is therefore our first hypothesis for ISS pathogenesis.

Second, several ISS-associated genes – GRIN1, GRIN2A, MAGI2, SPTAN1, and STXBP1 – are expressed in the pre- and/or postsynaptic membrane.18, 19, 20, 21 At the synapse a biologic relationship between ISS and autism is apparent, as several proteins associated with ISS interact with proteins implicated in autism pathogenesis.22, 23, 24, 25, 26 Forebrain synaptic dysfunction is therefore our second hypothesis for ISS pathogenesis.

Here, we present novel CNV data in 18 children with ISS, including 7 with deletion 1p36, and combine these with data from the literature to provide a more detailed bioinformatics analysis of gene content. We developed bioinformatics tools that integrate publicly available databases and network analysis algorithms to look for evidence of pathways of pathogenesis in ISS, and found enrichment for genes associated with ventral forebrain development and forebrain synaptic function, in addition to several other pathways.

Subjects and methods

CNVs associated with ISS

Novel ISS Cohort

Subjects with ISS were referred to the Infantile Spasms Registry and Genetic Studies (ARP) or to WBD for research analysis after abnormal findings on clinical chromosomal microarray (CMA). Our inclusion criteria consisted of diagnosis of ISS based on epileptic spasms with electrodecrement or diagnosis of other seizure type in the presence of hypsarrhythmia. Clinical CMA was performed on a variety of platforms according to the manufacturer's specifications as part of routine care. The inheritance of CNVs was established using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) on parental samples, except for LR09-044 where confirmation studies on parental samples were performed using the BlueGnome 180K array (Bouty Technogenetics, Milan, Italy). Subject LR11-055 was validated by D7S2476 and D7S3196 in parents, and subject LR11-056 was validated on a higher resolution 244K Agilent array. Inheritance of the duplication of 15q11q13 in subject IS09-007 from the maternal allele was demonstrated by genotyping of 21376915. The research protocols were approved by the IRB committees of the University of Chicago, the University of Washington, and Washington University.

Deletion 1p36-ISS cohort

Subjects with deletions of 1p36 and ISS were identified by chromosome analysis or subtelomere FISH. Informed consent was obtained to collect further clinical information or had previously been obtained as part of a long standing research project under one investigator, with informed consent in each case (LGS). Array CGH was performed using various versions of the SignatureChip (Signature Genomics, Spokane, WA, USA; see Table 2). Inheritance was established using FISH or genotyping with microsatellite markers on parental samples. To verify KLHL17 deletion in subject 1p09-C, STS (sequence-tagged site) markers were designed and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analyses were performed as described previously,27 using genomic DNA from the subject, her parents, hybrids containing the chromosome 1 with deletion from 1p09-C, and control DNA samples. These research studies were approved at Poznan University of Medical Sciences.

Published ISS loci

PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) was searched from 1975 to 2010 for all abstracts in English containing patient reports of ISS associated with a CNV or chromosomal translocation. Publications were included if the clinical information was sufficient to confirm a diagnosis of ISS by criteria stated above, the CNV or chromosomal translocation was de novo, and breakpoints could be obtained. The Decipher database (https://decipher.sanger.ac.uk/) was searched using the term ‘infantile spasms’, and the clinical and genomic data of identified subjects were examined.

Bioinformatics analysis of gene content

Evaluation for evidence of brain expression

The gene content from the loci of interest was extracted based on the hg18 version of the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu), using tools available through GEDI (http://gedi.ci.uchicago.edu/), and then handled with customized Perl and PHP scripts that interfaced with a MySQL database. Genes were evaluated for evidence of expression in the brain using the publicly available mouse databases in Supplementary Methods Table 1. Each gene was ranked for brain expression as yes, no, or unknown.

Evaluation for evidence of role in forebrain development/function

Genes with evidence of expression in the brain were then evaluated for a role in any of the eight steps of forebrain development and function, as detailed in the Supplementary Methods Table 2. This evidence was collected assisted by Pubmatrix (http://pubmatrix.grc.nia.nih.gov./) to carry out parallel searches of PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/), followed by manual review of the abstracts generated. Information about Gene Ontology (GO; http://geneontology.org) molecular function and biological process was also extracted with GEDI. A list of preliminary candidate genes for ISS was then compiled that had evidence for (1) expression in the brain followed by (2) role in one or more stages of forebrain development/function. These genes were termed preliminary candidate genes.

Evaluation for pathways of ISS pathogenesis

The list of preliminary candidate genes was then combined with the list of known ISS-associated genes and subjected to network analysis using String 8.3 (http://string-db.org/), an algorithm that mines publicly available protein–protein interaction data for direct and indirect associations.28 In order to minimize spurious associations, String analysis was performed with a confidence level of 0.9 (most stringent), and the Markov Clustering algorithm was used to identify the most relevant interactions.29 Additionally, GEDI functionality that integrates multiple sources of clinical, genomic, and biologic data were used to identify relationships between the preliminary candidate genes and potential pathways of ISS pathogenesis. To specifically evaluate the gene regulatory network of ventral forebrain development, the list of preliminary candidate genes was compared with the list of 84 genes differentially expressed in the forebrain of the Arx conditional knockout mouse.17 Genes shared in both lists were identified as potential genes interacting with this gene regulatory network. To specifically evaluate pathways of synaptic function, the list of preliminary candidate genes was compared with a list of 2912 genes extracted from GO that are involved in synaptic function (http://geneontology.org search on ‘synapse’) as well as the more specific child GO terms for synaptic transmission (GO:0007268), synaptic vesicle transport (GO:0048489), presynaptic membrane (GO:0042734), and postsynaptic density (GO:0014069). Genes present on overlapping lists were considered potential interactants in a specific synaptic biological process.

Statistical analysis

A Fisher's F-test was performed on the variance of the number of genes with role(s) in forebrain development that overlapped with pathways identified, compared with the variance in 200 genes with role(s) in forebrain development randomly selected from the BGEM data set (http://www.stjudebgem.org/web/mainPage/mainPage.php; Supplementary Table 4). A value of P<0.05 was used as an indicator of statistically significant enrichment for a pathway. Statistical analysis was performed using R version 2.9.2 (obtained from http://www.r-project.org/).

Results

CNVs associated with ISS

Novel ISS cohort

Eleven subjects had CNVs identified on clinical CMA. The clinical and laboratory data are summarized in Table 1, and the genomic data are illustrated in Supplementary Figure 1. All CNVs were confirmed to be de novo, with the exception of the large 21.5 Mb duplication of 2q24.3q32.1 in subject IS10-021, which was presumed to be de novo although confirmatory samples were not available from the phenotypically normal parents. We also note the association of ISS in subject LR11-055 with deletion of the Williams syndrome region 7q11.23, subject IS09-007 with duplication of maternal 15q11q13, and duplication of 21q21 in subject LR10-282. The entire gene content of each CNV was included for bioinformatics analysis, with the exception of subject IS10-028, as the ISS critical region for duplication 14q12 has been narrowed down to FOXG1.11 Clinical details are presented in the Supplementary Clinical Data.

Deletion 1p36-ISS cohort

Seven subjects with deletions of 1p36 and ISS were studied. The clinical and laboratory data are summarized in Table 2, and the genomic data are illustrated in Figure 1. We compared deleted regions in this cohort and concluded that KCNAB2, previously suggested as a candidate for epilepsy30 was not likely critical for ISS pathogenesis, as this gene was not deleted in subjects 1p73-C and 1p93-C. The commonly deleted region in all seven subjects includes another epilepsy candidate, GABRD. However, ISS were not present in five subjects with interstitial deletions including GABRD, and epilepsy was only present in two of those patients.31 In subject 1p09-C, STS marker walking confirmed deletion of another candidate, KLHL17 (data not shown). Subject 1p09-C had electroclinical features consistent with early infantile epileptic encephalopathy (EIEE, Ohtahara syndrome), illustrating the likely biologic similarities between EIEE and ISS. The gene content of the largest deletion in this cohort (1p105-C) was included in bioinformatics analysis. Clinical details for the deletion 1p36-ISS cohort are presented in the Supplementary Clinical Data.

Genomic data on seven subjects with deletion 1p36 and ISS (Del 1p36-ISS Cohort), comparing breakpoints with a previously reported subject (ISS reported),66 a subject with ISS and PMG,59 the PMG critical region,58 and five interstitial deletions without ISS but other forms of epilepsy variable.31 The region within the dashed line indicates plausible ISS critical region containing GABRD, with the solid region representing a smaller hypothesized critical region containing the synaptic-expressed KLHL17.

Published ISS loci

Our search of PubMed found 189 publications, of which 13 had data of sufficient detail to derive breakpoints, and in which the diagnosis was clearly ISS. Reports of Pallister–Killian syndrome and Down's syndrome were excluded because of the large number of genes. Three additional reports of balanced translocations in patients with ISS were identified, but in only one was the breakpoint mapped and the translocation disrupted a gene. Our search of Decipher (accessed January 2011) found 8 subjects reported with ISS, but only in subject 1229 was the CNV de novo. This subject with a 3.69-Mb deletion of 1p36 was previously reported,32 and did not have ISS but rather partial epilepsy, so this patient was not included (personal communication, K Devriendt). Altogether, the gene content from five published loci (Table 3) underwent bioinformatics analysis.

Bioinformatics analysis of gene content

Evaluation for evidence of brain expression

The 11 novel CNVs, the largest region from our deletion 1p36-ISS cohort, and the 5 published loci analyzed contained 521 genes (Supplementary Table 1). Evidence for brain expression was found for 230 genes (Supplementary Table 2). Evidence that a gene was not expressed in the brain was found for 94 genes, and no data were found for 197 genes. Therefore, 291 genes were excluded from further analysis.

Evaluation for evidence of role in forebrain development/function

Of the 230 genes with evidence for brain expression, 82 had evidence of a role in at least one of the eight steps of forebrain development or function (Supplementary Table 3). These 82 genes were termed preliminary candidate genes. On the basis of the information presented below, the candidate genes were further refined to those that were the best candidates (Table 4).

Evaluation for pathways of ISS pathogenesis

Network analysis on the list of preliminary candidate genes identified several pathways likely to be significant in neurodevelopment. These included gap junction signaling, WNT signaling, ERBB-family signaling, GDNF-family signaling, neuronal cell adhesion, semaphorin signaling, including, as expected, ventral forebrain development, and several pathways of forebrain synapse function. Network analysis on the larger list of brain-expressed genes was not informative, because of the incompleteness of data regarding detailed expression patterns for many of the genes (data not shown).

Ventral forebrain development

We explored the connection between the preliminary candidate genes and the gene regulatory network of ventral forebrain development in more detail because of the association of ARX, FOXG1, and MEF2C with ISS. An additional subject with duplication of FOXG1 at 14q12 is reported here. DLX1 and DLX2 were present within the large duplication of 2q24.3q32.1; these are transcription factors directly upstream of ARX. Additionally, two other genes within 2q24.3q32.1, GAD1 and PDK1 are important in GABAergic interneuron development.33 Finally, one of the preliminary candidate genes, MAGEL2, was differentially expressed in the Arx conditional knockout mouse and on this basis was considered a candidate for involvement in ventral forebrain development. Figure 2a illustrates this expanded gene regulatory network with these genes as proposed members. Our gene content was significantly enriched for members of this pathway (P<0.001).

(a) The expanded gene regulatory network for ventral forebrain development. ISS-associated genes are indicated by closed circles, candidate members of the network identified in this study are indicated by dashed circles. In the color version, red indicates gene deletion or intragenic mutation and green indicates gene duplication. Dashed lines represent putative gene regulatory relationships that require further validation. Figure generated using BioTapestry (http://www.biotapestry.org/). (b) Illustration of the GABA-receptor subunit genes expressed in the post-synapse with abnormal copy number in subjects with ISS identified in this study. The involvement of STXBP1 in synaptic vesicle exocytosis is also shown. Figure generated using ProteinLounge (http://www.proteinlounge.com/). GABA, gamma-aminobutyric acid; MGE, medial ganglionic eminence. The color reproduction of this figure is available at the European Journal of Human Genetics journal online.

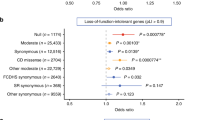

Forebrain synapse function

These pathways were first identified by the association of MAGI2, SPTAN1, and STXBP1 with ISS. During the course of this work, two additional genes expressed in the synapse were associated with ISS – GRIN112 and GRIN2A13 – providing additional validation for involvement of these pathways in ISS pathogenesis. In all, 15 of the 82 preliminary candidate genes overlapped with synaptic pathways. The presence of the GABRA5, GABRG3, and GABRB3 GABA receptor subunits in the 15q11q13 critical region suggests that abnormalities in GABAergic synapses have a role in ISS pathogenesis when duplicated from the maternal allele (Figure 2b). Additionally, copy number changes in several pre- and postsynaptic expressed genes were identified, including CRIPT, ERRB4, SNPH, and STX1A. Network analysis identified a functional relationship between SNPH and STX1A, which in turn interacts with the ISS-associated STXBP1 (Figure 3a). ERRB4 interacts with the postsynaptic density protein DLG4, which associates with the ISS-associated GRIN1 and GRIN2A (Figure 3b). KLHL17 is an actin-binding protein that interacts with GRIK2 in the postsynaptic density.34 Our gene content was significantly enriched for members of the pathway of synaptic vesicle transport (GO:0048489) (P<0.001).

(a) Protein–protein interaction network of synaptic vesicle exocytosis (GO:0016079), illustrating a relationship between ISS candidate SNPH with STX1A, which in turn interacts with the ISS-associated STXBP1. (b) Protein–protein interaction network of the postsynaptic density (GO:0014069), illustrating a relationship between ERBB4 with DLG4, which in turn interacts with the ISS-associated GRIN1 and GRIN2A.

Discussion

ISS are associated with copy number variations that provide evidence for pathogenesis

As these subjects were referred for study based on discovery of a pathogenic CNV, our data cannot be used to determine the frequency of pathogenic CNV in ISS. However, the data generally support the concepts that ISS have a genetic basis and that CNVs are relevant for study in children with this disorder. By analyzing the gene content in these CNVs, we present evidence to support at least two hypotheses of ISS pathogenesis, specifically abnormalities in ventral forebrain development and pathways of pre- and postsynaptic function.

Seven of the novel CNVs reported are microduplications, and assigning pathogenicity remains preliminary until more data exist on the effect of gene dosage on phenotype.35 More data are available regarding the effects of gene dosage in genomic microdeletions36 and we addressed these issues by examining DECIPHER for haploinsufficiency scores when compiling our list of ISS candidate genes.

ISS are part of a clinical spectrum of developmental epilepsies

The subjects in this report had a spectrum of developmental epilepsy related to ISS37 and included 13 children with ISS and hypsarrhythmia on EEG, 2 with other seizure types associated with hypsarrhythmia that we include based on previous studies,38 and 1 child with Ohtahara syndrome. Some of the subjects responded to standard ACTH therapy, while others developed intractable epilepsy. Several developed severe developmental impairment, autism, self-injurious behavior, or combinations of these problems. This is consistent with the clinical heterogeneity already described in patients with mutations in ISS-associated genes. Phenotype–genotype correlations are not possible with the subject numbers here, but correlations may emerge as larger patient numbers are ascertained. We also report ISS with hypsarrhythmia in a subject with duplication of 15q11q13, associating ISS with the most common chromosomal cause of autism.39 The finding of ISS in a subject with duplication of 21q21 may reduce the critical region for ISS in Down syndrome.

Enrichment of genes involved in ventral forebrain development within CNVs in ISS patients

As ARX was the first gene associated with ISS, much information is known about its role in ventral forebrain development. Arx-deficient mice have severe deficits in GABAergic interneurons while conditional mutants deleting Arx from ganglionic eminence-derived neurons have seizures similar to those observed in patients with ARX mutations.40, 41 Other genes important in ISS pathogenesis may be present in the regulatory network that directs ventral forebrain development, including FOXG1 upstream and MEF2C downstream. Duplications of FOXG1 at 14q12 have been associated with ISS,8, 11 and we report here an additional subject with this association. This study then identified candidate genes to expand this network further.

The presence of DLX1 and DLX2 within the large duplication of 2q24.3q32.1 suggests that copy number changes of genes linked in a functional network with ARX are involved in ISS pathogenesis. Mice lacking Dlx1 show loss of specific interneuron subtypes and have epilepsy,42 although there is not yet a phenotype described with duplication. Other genes interacting with ARX were identified to have abnormal copy number in ISS subjects. MAGEL2 is expressed in the developing hypothalamus,43 and is a candidate given the hypothesized role for abnormalities in the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and ACTH-responsiveness in ISS patients.44

Enrichment of genes involved in specific synaptic pathways within CNVs in ISS patients

One specific synaptic functional pathway, synaptic vesicle transport, and was enriched for genes with altered copy number in this study. SNPH has a role in presynaptic exocytosis,45 and Snph deletion in the mouse results in abnormal presynaptic function.46 CHL1 is a chaperon of the presynaptic SNARE complex.47 Additional genes expressed in the postsynaptic density/postsynaptic membrane, were of interest as well. CRIPT is involved in membrane support in close proximity to SHANK proteins.48, 49 We report the fourth patient with a deletion of 7q11.23 that does not include MAGI2,50, 51 raising the possibility that other genes, such as FZD9 and/or STX1A or other factors, may contribute to ISS in patients with Williams syndrome.

Genes were also identified with specific roles in GABAergic synapse function. ERBB4 is involved in GABAergic signaling in inhibitory interneurons,52 promotes interneuron migration, and is regulated by ARX.53 Several genes for GABA receptor subunits – GABRA5, GABRD, GABRG3, and GABRB3 – also had abnormal copy number in ISS subjects. GABRA5 is notably involved in interneuron function in the hippocampus.54 JAKMIP1 regulates GABRB2 mRNA, and can also be added to the list of genes involved in GABAergic synaptic function.55

ISS in deletion 1p36 patients associated with loss of KLHL17

As past reports indicated that 25% of deletion 1p36 syndrome patients may develop ISS,56 we wished to look closely at the gene content of deletion 1p36 subjects with ISS. The critical region(s) for ISS, and for epilepsy in general in deletion 1p36, have included GABRD and KCNAB230 as candidates. Our data suggest that in some subjects overlap exists with GABRD and KCNAB2, although a recent series of patients with GABRD deleted did not have ISS, and epilepsy in general was only variably present.31 Therefore, a more specific critical region for ISS derived from our data may include KLHL17. KLHL17 interacts with the kainate-type glutamate receptor subunit GRIK2, a key member of the postsynaptic density network centered on DLG4.34 KLHL17 also binds actin in the postsynaptic density,57 and may be involved in structural support of the postsynaptic membrane in a manner similar to the ISS-associated MAGI2.19 This candidate region overlaps partially with the critical region for polymicrogyria (PMG)58 and coincides with a reported deletion 1p36 patient with both PMG and ISS.59 These findings must be treated with caution, however, as position effect, incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity may have a role in epilepsy type in 1p36 deletion patients.

Abnormalities of forebrain synaptic growth and function suggest common biologic mechanism underlying both ISS and autism

Two themes emerged from these analyses: (1) pathways of GABAergic interneuron development and synaptic function may be linked in ISS pathogenesis; (2) several genes expressed in the presynaptic STX1A and SNARE complexes, as well as others in the postsynaptic density DLG4 complex, were identified with altered copy number in ISS subjects. These gene products are in close proximity to several autism-associated proteins. This leads to the hypothesis that abnormalities in proteins involved in forebrain GABAergic synaptic growth and function may form a common biologic mechanism underlying both autism and ISS, and that the increased prevalence of autism in children with a history of ISS may not be simply a result of epileptic encephalopathy.

In conclusion, we report 8 novel CNVs and additional children with 4 known CNVs from a group of 23 children with ISS and abnormal clinical CMA. We then used a novel bioinformatics approach to evaluate these CNVs to study several hypotheses of pathogenesis. We identified candidate genes and biologic pathways that will serve as targets for further validation studies. Finally, we argue that several of these biologic pathways of ISS pathogenesis are linked and involve forebrain GABAergic interneuron development, as well as GABAergic and other pathways of pre- and postsynaptic function.

References

Lux AL, Osborne JP : A proposal for case definitions and outcome measures in studies of infantile spasms and West syndrome: consensus statement of the West Delphi group. Epilepsia 2004; 45: 1416–1428.

Saemundsen E, Ludvigsson P, Rafnsson V : Risk of autism spectrum disorders after infantile spasms: a population-based study nested in a cohort with seizures in the first year of life. Epilepsia 2008; 49: 1865–1870.

Saitsu H, Kato K, Mizuguchi T et al: De novo mutations in the gene encoding STXBP1 (MUNC18-1) cause early infantile epileptic encephalopathy. Nat Genet 2008; 40: 782–788.

Strømme P, Mangelsdorf ME, Scheffer IE, Gécz J : Infantile spasms, dystonia, and other X-linked phenotypes caused by mutations in Aristaless related homeobox gene, ARX. Brain Dev 2002; 24: 266–268.

Kato M, Das S, Petras K, Sawaishi Y, Dobyns WB : Polyalanine expansion of ARX associated with cryptogenic West syndrome. Neurology 2003; 61: 267–276.

Weaving LS, Christodoulou J, Williamson SL et al: Mutations of CDKL5 cause a severe neurodevelopmental disorder with infantile spasms and mental retardation. Am J Hum Genet 2004; 75: 1079–1093.

Marshall CR, Young EJ, Pani AM et al: Infantile spasms is associated with deletion of the MAGI2 gene on chromosome 7q11.23-q21.11. Am J Hum Genet 2008; 83: 106–111.

Yeung A, Bruno D, Scheffer IE et al: 4.45 Mb microduplication in chromosome band 14q12 including FOXG1 in a girl with refractory epilepsy and intellectual impairment. Eur J Med Genet 2009; 52: 440–442.

Le Meur N, Holder-Espinasse M, Jaillard S et al: MEF2C haploinsufficiency caused by either microdeletion of the 5q14.3 region or mutation is responsible for severe mental retardation with stereotypic movements, epilepsy and/or cerebral malformations. J Med Genet 2010; 47: 22–29.

Saitsu H, Tohyama J, Kumada T et al: Dominant-negative mutations in alpha-II spectrin cause West syndrome with severe cerebral hypomyelination, spastic quadriplegia, and developmental delay. Am J Hum Genet 2010; 86: 881–891.

Brunetti-Pierri N, Paciorkowski AR, Ciccone R et al: Duplications of FOXG1 in 14q12 are associated with developmental epilepsy, mental retardation, and severe speech impairment. Eur J Hum Genet 2011; 19: 102–107.

Ding Y, Zhang Y, He B, Yue W, Zhang D, Zou L : A possible association of responsiveness to adrenocorticotropic hormone with specific GRIN1 haplotypes in infantile spasms. Dev Med Child Neurol 2010; 52: 1028–1032.

Endele S, Rosenberger G, Geider K et al: Mutations in GRIN2A and GRIN2B encoding regulatory subunits of NMDA receptors cause variable neurodevelopmental phenotypes. Nat Genet 2010; 42: 1021–1026.

Molinari F, Kaminska A, Fiermonte G et al: Mutations in the mitochondrial glutamate carrier SLC25A22 in neonatal epileptic encephalopathy with suppression bursts. Clin Genet 2009; 76: 188–194.

Hébert JM, Fishell G : The genetics of early telencephalon patterning: some assembly required. Nat Rev Neurosci 2008; 9: 678–685.

Colasante G, Sessa A, Crispi S et al: Arx acts as a regional key selector gene in the ventral telencephalon mainly through its transcriptional repression activity. Dev Biol 2009; 334: 59–71.

Fulp CT, Cho G, Marsh ED, Nasrallah IM, Labosky PA, Golden JA : Identification of Arx transcriptional targets in the developing basal forebrain. Hum Mol Genet 2008; 17: 3740–3760.

Ciufo LF, Barclay JW, Burgoyne RD, Morgan A : Munc18-1 regulates early and late stages of exocytosis via syntaxin-independent protein interactions. Mol Biol Cell 2005; 16: 470–482.

Deng F, Price MG, Davis CF, Mori M, Burgess DL : Stargazin and other transmembrane AMPA receptor regulating proteins interact with synaptic scaffolding protein MAGI-2 in brain. J Neurosci 2006; 26: 7875–7884.

Voas MG, Lyons DA, Naylor SG, Arana N, Rasband MN, Talbot WS : AlphaII-spectrin is essential for assembly of the nodes of Ranvier in myelinated axons. Curr Biol 2007; 17: 562–568.

Fan J, Vasuta OC, Zhang LY, Wang L, George A, Raymond LA : N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit- and neuronal-type dependence of excitotoxic signaling through post-synaptic density 95. J Neurochem 2010; 115: 1045–1056.

Craig AM, Kang Y : Neurexin-neuroligin signaling in synapse development. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2007; 17: 43–52.

Durand CM, Betancur C, Boeckers TM et al: Mutations in the gene encoding the synaptic scaffolding protein SHANK3 are associated with autism spectrum disorders. Nat Genet 2007; 39: 25–27.

Arking DE, Cutler DJ, Brune CW et al: A common genetic variant in the neurexin superfamily member CNTNAP2 increases familial risk of autism. Am J Hum Genet 2008; 82: 160–164.

Huang ZJ, Scheiffele P : GABA and neuroligin signaling: linking synaptic activity and adhesion in inhibitory synapse development. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2008; 18: 77–83.

Zhang C, Milunsky JM, Newton S et al: A neuroligin-4 missense mutation associated with autism impairs neuroligin-4 folding and endoplasmic reticulum export. J Neurosci 2009; 29: 10843–10854.

Gajecka M, Glotzbach CD, Jarmuz M, Ballif BC, Shaffer LG : Identification of cryptic imbalance in phenotypically normal and abnormal translocation carriers. Eur J Hum Genet 2006; 14: 1255–1262.

Jensen LJ, Kuhn M, Stark M et al: STRING 8—a global view on proteins and their functional interactions in 630 organisms. Nucleic Acids Res 2009; 37: D412–D416.

Brohée S, van Helden J : Evaluation of clustering algorithms for protein-protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinformatics 2006; 7: 488.

Heilstedt HA, Burgess DL, Anderson AE et al: Loss of the potassium channel beta-subunit gene, KCNAB2, is associated with epilepsy in patients with 1p36 deletion syndrome. Epilepsia 2001; 42: 1103–1111.

Rosenfeld JA, Crolla JA, Tomkins S et al: Refinement of causative genes in monosomy 1p36 through clinical and molecular cytogenetic characterization of small interstitial deletions. Am J Med Genet A 2010; 152A: 1951–1959.

Thienpont B, Mertens L, Buyse G, Vermeesch JR, Devriendt K : Left-ventricular non-compaction in a patient with monosomy 1p36. Eur J Med Genet 2007; 50: 233–236.

Oishi K, Watatani K, Itoh Y et al: Selective induction of neocortical GABAergic neurons by the PDK1-Akt pathway through activation of Mash1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009; 106: 13064–13069.

Salinas GD, Blair LA, Needleman LA et al: Actinfilin is a Cul3 substrate adaptor, linking GluR6 kainate receptor subunits to the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. J Biol Chem 2006; 281: 40164–40173.

Berg JS, Potocki L, Bacino CA : Common recurrent microduplication syndromes: diagnosis and management in clinical practice. Am J Med Genet A 2010; 152A: 1066–1078.

Huang N, Lee I, Marcotte EM, Hurles ME : Characterising and predicting haploinsufficiency in the human genome. PLoS Genet 2010; 6: e1001154.

Djukic A, Lado FA, Shinnar S, Moshé SL : Are early myoclonic encephalopathy (EME) and the Ohtahara syndrome (EIEE) independent of each other? Epilepsy Res 2006; 70 (Suppl 1): S68–S76.

Philippi H, Wohlrab G, Bettendorf U et al: Electroencephalographic evolution of hypsarrhythmia: toward an early treatment option. Epilepsia 2008; 49: 1859–1864.

Depienne C, Moreno-De-Luca D, Heron D et al: Screening for genomic rearrangements and methylation abnormalities of the 15q11-q13 region in autism spectrum disorders. Biol Psychiatry 2009; 66: 349–359.

Marsh E, Fulp C, Gomez E et al: Targeted loss of Arx results in a developmental epilepsy mouse model and recapitulates the human phenotype in heterozygous females. Brain 2009; 132: 1563–1576.

Price MG, Yoo JW, Burgess DL et al: A triplet repeat expansion genetic mouse model of infantile spasms syndrome, Arx(GCG)10+7, with interneuronopathy, spasms in infancy, persistent seizures, and adult cognitive and behavioral impairment. J Neurosci 2009; 29: 8752–8763.

Cobos I, Calcagnotto ME, Vilaythong AJ et al: Mice lacking Dlx1 show subtype-specific loss of interneurons, reduced inhibition and epilepsy. Nat Neurosci 2005; 8: 1059–1068.

Lee S, Walker CL, Wevrick R : Prader-Willi syndrome transcripts are expressed in phenotypically significant regions of the developing mouse brain. Gene Expr Patterns 2003; 3: 599–609.

Frost JD, Hrachovy RA : Pathogenesis of infantile spasms: a model based on developmental desynchronization. J Clin Neurophysiol 2005; 22: 25–36.

Boczan J, Leenders AGM, Sheng Z : Phosphorylation of syntaphilin by cAMP-dependent protein kinase modulates its interaction with syntaxin-1 and annuls its inhibitory effect on vesicle exocytosis. J Biol Chem 2004; 279: 18911–18919.

Kang J, Tian JH, Pan PY et al: Docking of axonal mitochondria by syntaphilin controls their mobility and affects short-term facilitation. Cell 2008; 132: 137–148.

Andreyeva A, Leshchyns’ka I, Knepper M et al: CHL1 is a selective organizer of the presynaptic machinery chaperoning the SNARE complex. PLoS One 2010; 5: e12018.

Passafaro M, Sala C, Niethammer M, Sheng M : Microtubule binding by CRIPT and its potential role in the synaptic clustering of PSD-95. Nat Neurosci 1999; 2: 1063–1069.

Valtschanoff JG, Weinberg RJ : Laminar organization of the NMDA receptor complex within the postsynaptic density. J Neurosci 2001; 21: 1211–1217.

Röthlisberger B, Hoigné I, Huber AR, Brunschwiler W, Capone Mori A : Deletion of 7q11.21-q11.23 and infantile spasms without deletion of MAGI2. Am J Med Genet A 2010; 152A: 434–437.

Komoike Y, Fujii K, Nishimura A et al: Zebrafish gene knockdowns imply roles for human YWHAG in infantile spasms and cardiomegaly. Genesis 2010; 48: 233–243.

Neddens J, Buonanno A : Selective populations of hippocampal interneurons express ErbB4 and their number and distribution is altered in ErbB4 knockout mice. Hippocampus 2010; 20: 724–744.

Zhao Y, Flandin P, Long JE, Cuesta MD, Westphal H, Rubenstein JL : Distinct molecular pathways for development of telencephalic interneuron subtypes revealed through analysis of Lhx6 mutants. J Comp Neurol 2008; 510: 79–99.

Glykys J, Mann EO, Mody I : Which GABA(A) receptor subunits are necessary for tonic inhibition in the hippocampus? J Neurosci 2008; 28: 1421–1426.

Costa V, Conte I, Ziviello C et al: Identification and expression analysis of novel Jakmip1 transcripts. Gene 2007; 402: 1–8.

Bahi-Buisson N, Guttierrez-Delicado E, Soufflet C et al: Spectrum of epilepsy in terminal 1p36 deletion syndrome. Epilepsia 2008; 49: 509–515.

Chen Y, Derin R, Petralia RS, Li M : Actinfilin, a brain-specific actin-binding protein in postsynaptic density. J Biol Chem 2002; 277: 30495–30501.

Dobyns WB, Mirzaa G, Christian SL et al: Consistent chromosome abnormalities identify novel polymicrogyria loci in 1p36.3, 2p16.1-p23.1, 4q21.21-q22.1, 6q26-q27, and 21q2. Am J Med Genet A 2008; 146A: 1637–1654.

Saito Y, Kubota M, Kurosawa K et al: Polymicrogyria and infantile spasms in a patient with 1p36 deletion syndrome. Brain Dev 2011; 33: 437–441.

Gajecka M, Glotzbach CD, Shaffer LG : Characterization of a complex rearrangement with interstitial deletions and inversion on human chromosome 1. Chromosome Res 2006; 14: 277–282.

Kubo T, Kakinuma H, Nakamura T, Kitatani M, Ozaki M, Takahashi H : Infantile spasms in a patient with partial duplication of chromosome 2p. Clin Genet 1999; 56: 93–94.

Gérard-Blanluet M, Romana S, Munier C et al: Classical West ‘syndrome’ phenotype with a subtelomeric 4p trisomy. Am J Med Genet A 2004; 130A: 299–302.

Schneider A, Benzacken B, Guichet A et al: Molecular cytogenetic characterization of terminal 14q32 deletions in two children with an abnormal phenotype and corpus callosum hypoplasia. Eur J Hum Genet 2008; 16: 680–687.

Auvin S, Holder-Espinasse M, Lamblin M, Andrieux J : Array-CGH detection of a de novo 0.7-Mb deletion in 19p13.13 including CACNA1A associated with mental retardation and epilepsy with infantile spasms. Epilepsia 2009; 50: 2501–2503.

Backx L, Ceulemans B, Vermeesch JR, Devriendt K, Van Esch H : Early myoclonic encephalopathy caused by a disruption of the neuregulin-1 receptor ErbB4. Eur J Hum Genet 2009; 17: 378–382.

Bursztejn AC, Bronner M, Peudenier S, Gregoire MJ, Jonveaux P, Nemos C : Molecular characterization of a monosomy 1p36 presenting as an Aicardi syndrome phenocopy. Am J Med Genet A 2009; 149A: 2493–2500.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the families of the subjects who enrolled in this study. The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health including NINDS Neurologic Sciences Academic Development Award K12 NS001690-12 to ARP and R01-NS046616 to WBD; Washington University Children's Discovery Institute, Grant MD-F-2010-62 to ARP; and the Ministry of Education and Science, Poland, Grant NN 301238836 to MG.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on European Journal of Human Genetics website

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Paciorkowski, A., Thio, L., Rosenfeld, J. et al. Copy number variants and infantile spasms: evidence for abnormalities in ventral forebrain development and pathways of synaptic function. Eur J Hum Genet 19, 1238–1245 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2011.121

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2011.121

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

KLHL17/Actinfilin, a brain-specific gene associated with infantile spasms and autism, regulates dendritic spine enlargement

Journal of Biomedical Science (2020)

-

6q22.1 microdeletion and susceptibility to pediatric epilepsy

European Journal of Human Genetics (2015)

-

Genomic analysis identifies candidate pathogenic variants in 9 of 18 patients with unexplained West syndrome

Human Genetics (2015)

-

A genomic copy number variant analysis implicates the MBD5 and HNRNPUgenes in Chinese children with infantile spasms and expands the clinical spectrum of 2q23.1 deletion

BMC Medical Genetics (2014)

-

Genotype–phenotype correlation in interstitial 6q deletions: a report of 12 new cases

neurogenetics (2012)